Contra Rubin et al on genetic interations

[single_cell In the Maehr lab’s regular journal club, we recently discussed a Cell paper from the research groups of Howard Chang, Will Greenleaf, and Paul Khavari (henceforth “Rubin et al.”).

Rubin, A. J., Parker, K. R., Satpathy, A. T., Qi, Y., Wu, B., Ong, A. J., … & Zarnegar, B. J. (2019). Coupled single-cell CRISPR screening and epigenomic profiling reveals causal gene regulatory networks. Cell, 176(1-2), 361-376.

It’s an impressive technical feat. In non-technical terms, they can study the accessibility of DNA – the packaging – in individual cells under a variety of artificially manipulated conditions. In jargon, they combine pooled CRISPR knockdowns and knockouts with a single-cell ATAC-seq readout. It’s a whopper of a paper, with tons of information and very complicated analyses. Unfortunately, there’s a crucial bit of interpretation that is, IMHO, just plain wrong… and it’s the main point of the paper.

Statistical interactions are not genetic interactions

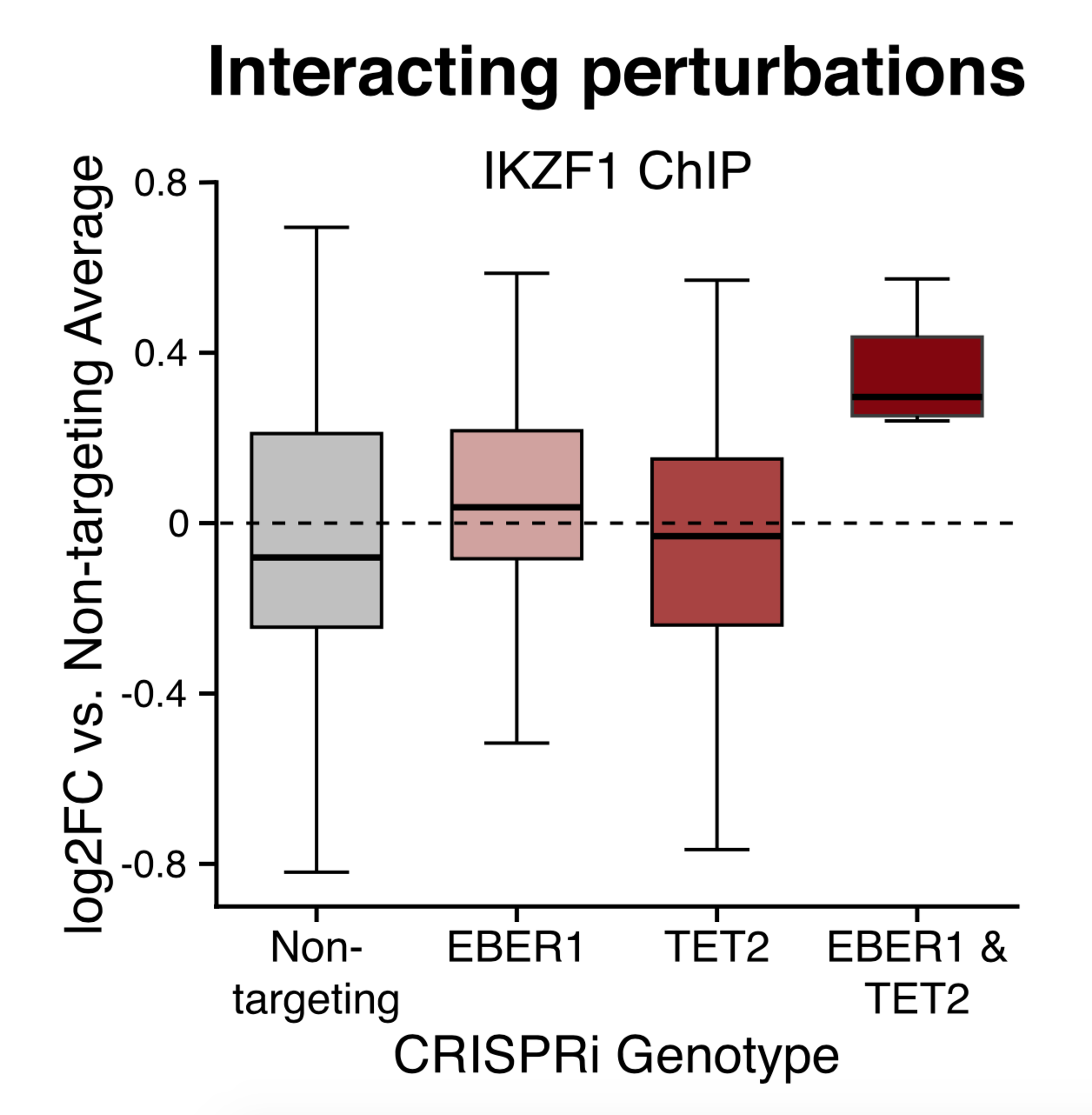

Their figures 4 and 7 are themed around genetic interactions. They knock down Gene A and Gene B separately, then predict what the joint effects would be. Then they test their predictions by knocking down A and B in the same set of cells. Here is an example (their figure 4B); they describe this as an interaction.

Unfortunately, “interaction” means one thing when you’re writing down regression models and another when you’re drawing biochemical networks. They gloss over this difference and get the biology wrong. In the statistical sense, they are right to call it an interaction: a model with terms for EBER1 and TET2 won’t fit the data very well, and an “interaction term” is needed:

\[\beta_0 + \beta_{EBER1} + \beta_{TET2} \not\approx Y_{both}\]-

\[\beta_0 + \beta_{EBER1} + \beta_{TET2} + \beta_{EBER1, TET2} \approx Y_{both}\]But in biochemistry, EBER1 is a non-coding RNA, and TET2 is a protein. An interaction means they interact physically, for instance if one binds to and degrades the other. The simplest biological model compatible with their data does not require any physical interaction between EBER1 and TET2. In fact, using the typical language of gene knockouts, TET2 and EBER1 are redundant. Successful repression of the loci in question can be carried out by EBER1, even when TET2 is gone, and by TET2, even without EBER1. Repression fails only when both EBER1 and TET2 are removed. Since each one works without the other present, this actually argues against physical binding between them.

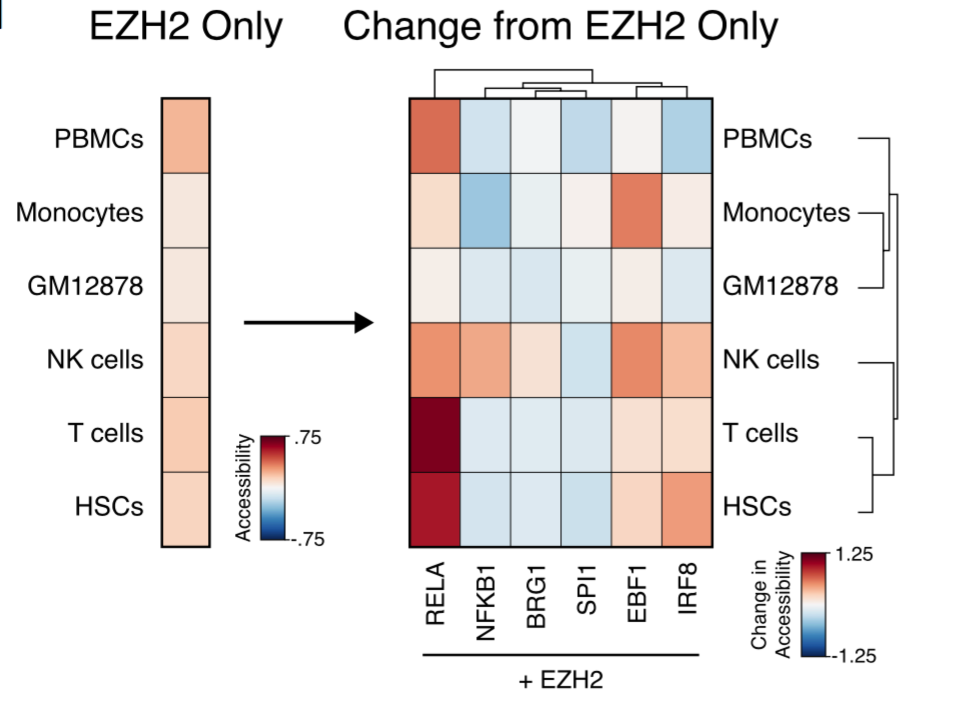

Rubin et al repeat this mistake further down when discussing EZH2, saying it “cooperates” with EBF1, IRF8, and RELA to prevent stem cells from entering certain specialized lineages. But their figure specifically indicates differences observed between two groups that both have EZH2 knockdowns.

So each of these extra factors works even in the absence of EZH2. Rather than facilitating each others’ actions, these genes are working independently towards the same end.

An improved set of concepts to relate multiple perturbations with biochemical interactions

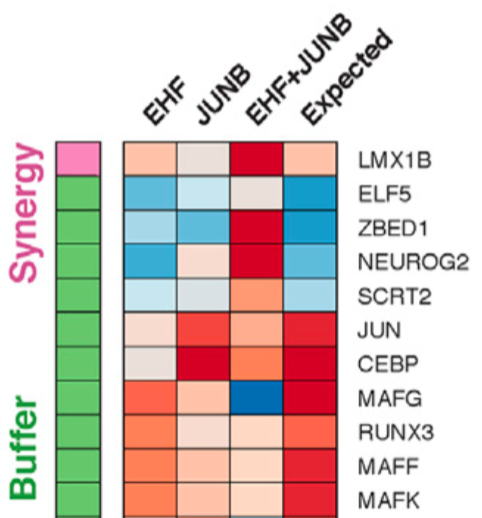

In figure 7, Rubin et al go on to classify dozens of pairs of knockouts by the (statistical) interactions or lack thereof.

They seem to borrow terminology from Dixit et al 2016, who write:

For each pair of perturbed TFs, we assessed the relative proportion of target genes where their relation is additive (no interaction), synergistic, buffering (antagonistic), or dominant (when the two factors have opposing effects and the interaction term enhances one of them).

These terms are a creative, quick way to give practical meaning to regression results that are otherwise biologically opaque. But, if we are going to start cataloguing genetic interations, it’s time to replace them with something more detailed and mechanistic.

How? First, we need to stop using only the interaction term of the regression. We must consider activity in all four settings: the control, knockdown of gene A alone, knockdown of of gene B alone, and knockdown of both genes together. Once we have all the information, we can posit mechanistic models and see which ones fit the data. Here are the terms I would use.

A and B form a complex activating the target. \

The complex require both pieces to work. | + | - | - | -

B maintains the target's activity alone. | + | + | - | -

A maintains the target's activity alone. | + | - | + | -

??? | + | - | - | +

A and B are redundant. | + | + | + | -

??? | + | + | - | +

??? | + | - | + | +

If you see the inverse of a pattern from the table, just replace “activating” or “activity” with “repressing” or “repression”. In my opinion, if two factors are redundant, there is no particular reason to suspect they form a complex together. I would expect most complexes require all of their components, meaning the components are non-redundant.

Fin

Does anyone have biological examples of behavior falling under the “???” categories? Drop me a line and explain what you think is going on.

P.S. What I like about this paper

Let’s be clear: despite my disagreement with their terms, I am a huge fan of this paper. It’s technically impressive and thoughtful. One really cool detail is their trick for increasing statistical power: they claim to see meaningful results with as few as five cells (five! five!) for any given perturbation. The trick is to average data across locations on the genome that share binding motifs for a transcription factor under study. This turns the analysis from something noisy and difficult to interpret – a bunch of weak signals at mostly in non-coding regions of unknown function – into something intuitive: a measure of protein activity for a relatively well-studied transcription factor.