Wellness rewards programs allow discrimination (technical appendix)

[misc This is not a stand-alone post. It is a technical appendix for an upcoming post, which is (EDIT) now published here on the blog of the peer-reviewed journal Medical Care!

Appendix 1: Accuracy of Li et al’s healthy eating index as a Black-White classifier

Here is the Li et al paper referenced in my original post.

Li, W., Youssef, G., Procter-Gray, E., Olendzki, B., Cornish, T., Hayes, R., … & Magee, M. F. (2017). Racial differences in eating patterns and food purchasing behaviors among urban older women. The journal of nutrition, health & aging, 21(10), 1190-1199.

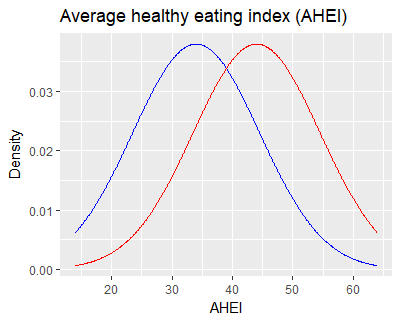

Li et al. includes an overall Average Healthy Eating Index, for which the higher-scoring group (p < 0.001) was White participants. Li & coauthors report group means of 44 and 34 points with standard deviations of 10.5. (I’m rounding the numbers.) If the scores were perfectly Normally distributed, it would give an overlap that looks like this.

In Washington D.C., where Li & coauthors’ study recruited, Black and White populations each make up roughly 45% of the city, so it’s fair to put the same area under the curves even though that wouldn’t make sense nation-wide. Dropping a decision boundary midway at 39 gives a Black-White classifier with about 68% accuracy, compared to 50% by chance.

The assumption of normally distributed scores is not reasonable, and it could bias the estimate in either direction, but when I replace the normal distribution with a right-skewed Gamma distribution having the same mean and sd, the numbers hardly change. You can see my calculations and reproduce the plot with this R script.

A bigger issue: it’s unclear how statistical trends will change when expanded from ~100 older women in DC to national-level or regional-level wellness vendors. This is why I cited the Food Trust review article as well.

Appendix 2: On counterfactual fairness

Here is the counterfactual fairness paper by James Kusner and colleages.

Kusner, M. J., Loftus, J., Russell, C., & Silva, R. (2017). Counterfactual fairness. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 4066-4076).

They advocate for the following definition of “Counterfactual Fairness”. $Y$ represents the variable being predicted – for instance, yearly healthcare costs. $X$ represents the data used to make the prediction – for instance, grocery purchases. $A$ represents a protected attribute such as race or gender. $\hat Y$ is the prediction of $Y$. $\hat Y_{A\leftarrow a’}$ represents a counterfactual prediction for someone whose race and/or gender has been magically altered. For all possible values of $x$, $a$, and $a’$, the criterion demands $\Pr(\hat Y \mid X=x, A=a ) = \Pr(\hat Y_{A\leftarrow a’} \mid X=x, A=a )$ .

In plain English, if you alter someone’s gender identity or racial/ethnic background (for example), it should not affect the predictions made about them. Using typical causal statistics jargon, I’ll call this an “intervention.” For biological/physical sex, the intervention might be to roll back time to when someone is conceived and replace the paternal X chromosome with the paternal Y chromosome or vice versa.

A key aspect of this definition is that you must allow the intervention’s effects to propagate. For the case of biological/physical sex, the intervention happens at conception, and a fair prediction should be invariant to all the resulting changes in either life experience or innate characteristics.

For a concept like race, which is not biological but rather tied up with culture, history, and perceptions of others, it is not clear to me what the intervention is. After studying the article, I conclude that it would be far-reaching. Kusner et al specify that the set of protected characteristics needs to be ancestrally closed with respect to the underlying causal graph. In plain English, that means if race is protected, so are “mother’s race”, “father’s race”, and so on. This has massive implications when applying the criterion to race as a protected attribute. If you want your prediction system to meet Kusner et al’s standard of racial equity, you should imagine the intervention happening generations ago, with all the cascading experiences of racial identity over centuries. Your predictions should still come out the same.

Appendix 3: More on counterfactual fairness

Why do we have to completely avoid using diet in our predictions, just because it has been affected by racial / cutural history? In the counterfactual fairness paper, Lemma 1 and the discussion surrounding it answers this question. The only practical way to avoid flunking the criterion is to avoid variables that are downstream of protected attributes in the causal graph. Although this is not mathematically necessary in situations where the causal model is completely specified, it’s necessary in real life, where the causal model is murky.