We predict that the transcript abundance from the gene we are knocking down will (checks notes) decrease

[single_cell grn stat_ml - The problem with gene-wise characterization of genetic interventions

- So, most benchmarks are addressing this problem, right?

- A classical solution: conditioning

- Appendix: retrieval metrics and the targeted gene

The problem with gene-wise characterization of genetic interventions

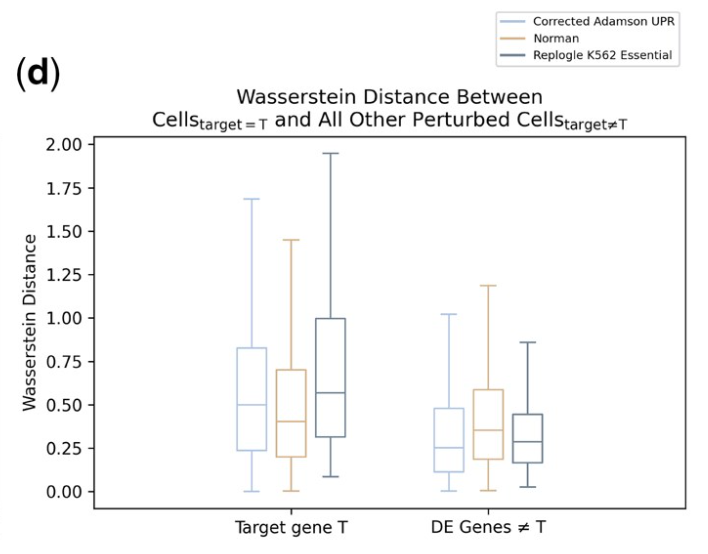

When you target a gene with CRISPRi, or something, its transcript goes down (or up). Actually, it goes down (or up) a very, very large amount. It goes down (or up) farther than most other genes; see figure 1d of Wong et al..

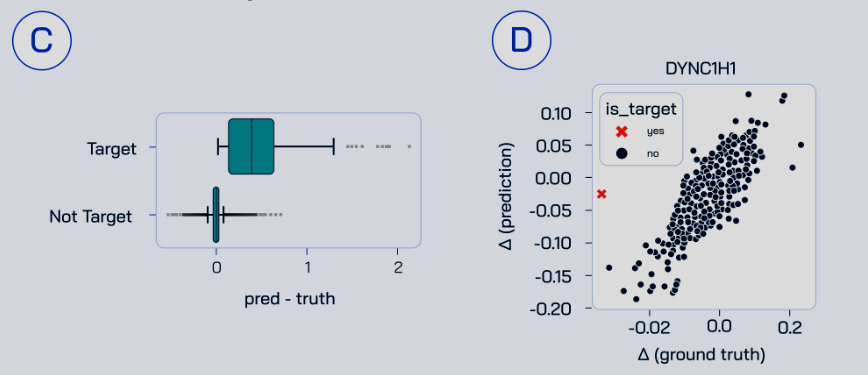

It goes down (or up) radically farther than biologically-oriented models expect: see figure 5C,D of the TxPert paper.

(This post is part of a series on prediction of gene expression in response to genetic perturbations, which is often called virtual cell modeling.)

- Episode 1: methods circa mid-2024

- Episode 2: benchmarks circa early 2025

- Episode 3: a broader look at genomic foundation models (large-scale, multi-purpose neural networks trained on DNA or RNA data)

- Episode 4: new developments circa June 2025 (this post)

- Episode 5: a snippet on weird behavior of MSE

- Episode 6: a rant on biological versus technical effects (this post)

Hitting the target is a technical matter; it has nothing to do with the biology we are interested in. The natural regulation of the targeted gene is completely subverted. For CRISPRi, some of the strongest human repressors, KRAB or KRAB+MECP2, are delivered straight to your doorstep (free shipping if you pay for Prime… editing… I’ll see myself out). For CRISRPa, four copies of the famously potent activator VP16 are often used. For CRISPR, a double-strand break is introduced that renders the protein product of the gene non-functional. This usually lowers the mRNA abundance, and it always uncouples the mRNA abundance from its typical (hopeful) interpretation as a proxy for gene activity.

These effects are profoundly unnatural. KRAB occurs in the human genome only as a domain of other proteins, not independently. VP16 is not even a human protein; it comes from herpes. CRISPR was famously discovered in the bacterium S. pyogenes. And regardless of their origin, deploying these factors to an arbitrary gene is totally artificial. The question of effects on a directly targeted gene is a technical matter. It is relevant to epigenetic engineering, but it is not a primary goal of perturb-seq’s drug discovery applications.

If the target gene’s expression tells us nothing about biology, then it tells us nothing about the ideal performance of a virtual cell model. Thus, some of the largest effects in our data are not the effects we should be using to judge our models.

This presents an opportunity for reward hacking. Including or excluding the directly targeted gene(s) in each sample can affect relative performance of models and baselines. This is a central message of Wong et al.’s work. This is especially critical when selecting the top 20 most differentially expressed genes over the control: as shown by Csendes et al, the top 20 often include the directly targeted gene, and excluding the directly targeted gene can reverse your overall conclusion. The Arc competition heeded these warning signs, excluding the directly targeted gene from their PDS sub-score (though this is complicated; see appendix).

So, most benchmarks are addressing this problem, right?

I have found no mention of this topic in:

- Ahlmann-Eltze et al.

- PerturBench’s Oct 2025 update

- PertEval-scFM’s May 2025 update

- scEval

- C. Li et al.

- L. Li et al’s Sep 2025 update

- Systema

- Diversity by Design

- Deep Learning-Based Genetic Perturbation Models Do Outperform Uninformative Baselines on Well-Calibrated Metrics.

This may not matter for metrics like MSE or MAE that dilute the target-gene effect with lots of other non-targeted genes. But Wong’s and Csendes’s teams showed it can make or break SOTA for retrieval metrics, as well as metrics that isolate or up-weight the genes that are most differentially expressed. This problem needs to be addressed.

A classical solution: conditioning

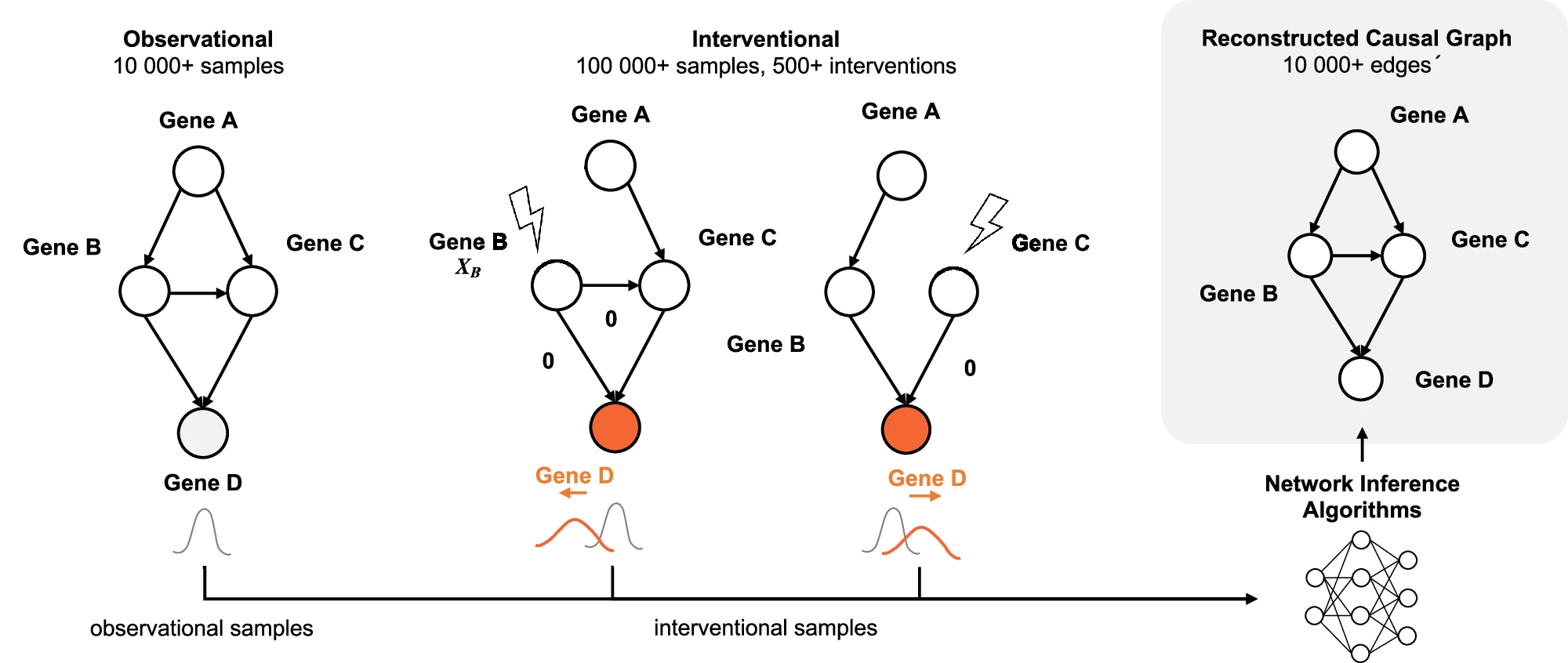

If you write out the probability distribution of a transcript count vector as $P(T)P(X\vert T)$, where T is the count of the directly perturbed gene(s) and X is the count of everything else, we should be using $P(X\vert T)$, not $P(T)$. To a causal statistics person, this is a natural decomposition: it corresponds to an “intervention graph”, which is like a gene regulatory network where the incoming edges are removed from the perturbed gene. Chevalley et al. 2025 provide a great visual.

So, let’s estimate $P(X\vert T)$, not $P(X,T)$. During training, that means you don’t need to minimize the loss on the gene that was perturbed. During evaluation, it means you shouldn’t get extra points for predictions about $P(T)$. And when you make predictions conditional on T, you can actually reveal T to the predictor. Similar to a supervised ML benchmark where you reveal the test-set features to each competitor, you might as well reveal the post-perturbation expression level of the directly targeted gene to your virtual cell algorithms. (For knockouts, you should set T to 0 prior to any training or testing; some transcript may be present but it won’t code for a functional protein.) We did this in PEREGGRN, and thanks to thoughtful feedback, we did a better job explaining and emphasizing our choice in the SHINY NEW JOURNAL VERSION LOOK AT ME LOOK AT ME. I think it’s a nice solution that deserves wider adoption.

Appendix: retrieval metrics and the targeted gene

Suppose I look at retrieval and I compare predictions P1, P2, P3 against true profile T1, or I compare P1 to T1, T2, T3. For a given comparison, multiple genes are among those targeted, and this causes weird gotchas.

- Should the calculation for distance of P[i] to T[j] exclude both genes i and j? You could rank by $d_{-i,-j}(P[i], T[j])$ across all $j$. But then you are head-to-head comparing different notions of distance … and the desired winner has one more dimension than everyone else. Also, what if gene $j$ has extremely high variance for some values of $j$? Anyone who gets to exclude it gets an undue advantage.

- Should all distance calculation exclude all directly targeted genes? Then you exclude a lot of interesting and useful info.

I have a proposal for how to fix this. The position of one item in a ranked list can be determined by comparing its value to each other item in the list. For all $j\neq i$, check if $d_{-i,-j}(P[i], T[i]) < d_{-i,-j}(P[i], T[j])$ where $d_{-i,-j}$ is a distance that ignores genes $i$ and $j$. Each individual comparison is fair, and the end result is similar to existing retrieval metrics.

As far as I can tell, most work excludes neither gene $i$ nor gene $j$, and the Arc challenge excluded i but not j (their retrieval metric was oriented like P1 to T1, T2, T3). I don’t see a clean way out of this via conditioning.